Beyond Trauma: Re-Visioning Trauma Therapy

What would therapy look like if it wasn’t centered around childhood trauma?

Since publishing my recent article on The Rise of Traumadelic Culture I’ve heard from a lot of people who have also begun to see the limitations of trauma-centered approaches to therapy and have started to question some of the leading voices and dominant narratives associated with it.

They want to break free, but can’t imagine what might be beyond trauma-centered therapy, or what might replace it. The cultish ideology around childhood trauma has infected psychotherapy to such a degree that many people can’t envision a therapy that’s not trauma-centered. Many people have been asking me, “What would therapy even look like if it’s not centered around childhood trauma?”

An answer to that question can be found throughout my work over the past few years, but I don’t expect many people will take the time to try and piece some together some kind of answer from all the breadcrumbs I’ve scattered about. So rather than try and respond to each person individually or expect that they’ll dive deeply into the books, articles and podcasts I’ve made to explore a deeper approach to healing, growth and transformation, I thought it’d be helpful to try and summarize my ideas and approach in a (somewhat) short article.

That said, don’t expect a simple step-by-step explanation. One of the major limitations of the trauma-centered approach is that it’s overly reductive and relies too much on simplistic causal explanations. “This symptom is a result of this trauma. Here are some tools to heal the trauma.” That kind of formulaic framework helps new therapists feel more confident and secure, but isn’t the real attraction of any religious doctrine or ideology that it offers easy answers to complex questions?

So I’m not even gonna go there.

What I will try to do instead is describe another orientation, one that is neither trauma-centered, nor about “getting past” trauma or “leaving it behind.”

In this approach that I’m proposing, the painful experiences of the past are integrated into a much larger story than what trauma therapy usually provides. In most trauma therapy models, you are either Hero or Victim. Both are limiting stories that trap a person in a juvenile, pre-initiatory stage of development because they’re still attached to the Child archetype.

The Hero has had his time in the sun. The Victim has spent enough time in the dark. In order to outgrow these limiting archetypes, we must reclaim more complex and mature stories to guide our individual lives and the transformation of culture.

In order for you to break the spell of Traumadelic Culture and share in an alternate vision with me, it’ll require a leap of imagination and the courage to question the fundamental beliefs of our rational, materialist, consumer culture. Along the way, we’ll follow in the footsteps of trailblazers Carl Jung, James Hillman and UG Krishnamurti and the well-laid tracks put down by the age-old traditions of yoga and shamanism.

Yoga, shamanism and archetypal psychology are three pathways that helped me see trauma and healing in a way that deviates from conventional Western scientific models and theories and contributed to my overall therapeutic approach. I’ll touch on each of them briefly in this article, and offer some recommended reading at the end if you want to explore the particular lineages I refer to in more depth.

Just in case it needs to be said at this point: yes, trauma is real. One of my problems with the Trauma Cult is that they have inflated the word trauma to such a degree that it’s lost any real meaning. Because it could mean anything, it means nothing. This is problematic for many reasons, including the diminishment of real traumas caused by war, violent assault etc. Therapy used to at least distinguish between “big T” traumas and “little T” traumas, but even those qualifiers have been swallowed up by Trauma as an all-encompassing descriptor that erases and smoothes over all the details of what happened. It can be used as a defence, or for self-inflation. I’d like to see the word reserved for its original diagnostic meaning, “Trauma is an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, crime, or natural disaster” (American Psychological Association), and find more creative and precise language to talk about the difficult and painful experiences we all experience as children and adults.

A Radical Reorientation Toward Life

“The plain fact is that if you don’t have a problem, you create one. If you don’t have a problem you don’t feel that you are living.”

— U.G. Krishnamurti

I suppose my own orientation started to become clear when I began studying and practicing yoga with more dedication and enthusiasm.

About 7 or 8 years ago I apprenticed with an elderly yoga teacher who, back in the 80s, followed the “anti-guru” Indian philosopher UG Krishnamurti, a contemporary (and rival) of the more famous Krishnamurti, Jiddu. My teacher would often quote UG and tell stories about what it was like to be with him — “It was like being with a cat — no agenda!”. During that period I spent quite a lot of time reading books written by UGs friends and listening to old interviews with him.

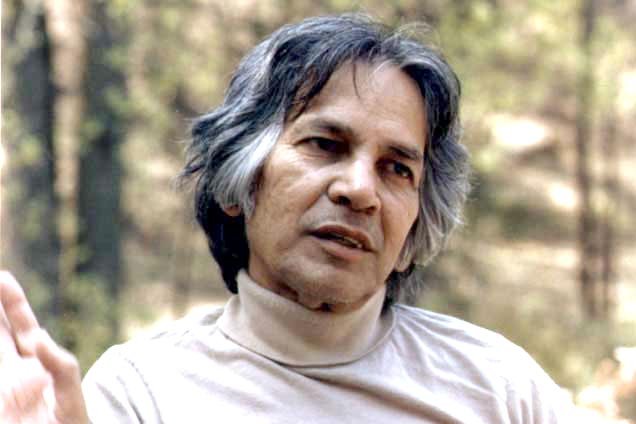

Uppaluri Gopala Krishnamurti (1918-2007)

When I listened to UG, I sometimes found it difficult to follow his arguments and he often came across to me as an angry, bitter guy who delighted in “blasting” the people who came to him hungry for answers to their spiritual questions. Still, some kind of transmission occurred. I vividly remember one night in particular when I half-woke from sleep, lying in bed with my whole body subtly vibrating.

As I lay there feeling a strong energy course through my body, I had a vision of all these thought forms arising and falling within an infinite inner space. As each identity or belief construct fell away, I felt such an effervescent joy bubble up that I had to laugh. For some time, I lay there giggling at how silly I had been, and how silly the human condition is. These ideas about who I am, what the world is all about…just falling away, like there was nothing to them.

Immediately and tangibly, I understood what UG meant by “the mind is a myth.” What we think of as “my mind” or “my self” are merely a collection of stories we tell ourselves and others in an attempt to avoid what psychologist James Hollis calls “the three As”: ambiguity, ambivalence and anxiety. In our quest to avoid the three As we seek their opposites, what I call “the three Cs”: certainty, clarity and calm.

Here’s an excerpt from Mind Is A Myth, a collection of conversations with UG:

“Your problems continue because of the false solutions you have invented. If the answers are not there, the questions cannot be there. They are interdependent; your problems and solutions go together. Because you want to use certain answers to end your problems, those problems continue.

The numerous solutions offered by all these holy people, the psychologists, the politicians, are not really solutions at all. That is obvious. If there were legitimate answers, there would be no problems. They can only exhort you to try harder, practice more meditations, cultivate humility, stand on your head, and more and more of the same. That is all they can do.

The teacher, guru, or leader who offers solutions is also false, along with his so-called answers. He is not doing any honest work, only selling a cheap, shoddy commodity in the marketplace. If you brushed aside your hope, fear, and naïveté‚ and treated these fellows like businessmen, you would see that they do not deliver the goods, and never will. But you go on and on buying these bogus wares offered up by the experts.”

Even though I got the idea that many of our so-called problems are manufactured to keep us in a disempowered, consumer role, I couldn’t help but wonder if there still wasn’t something we could do about it. I suspected that one of the reasons why UG seemed so angry was that he was frustrated that he wasn’t getting through to his followers. It’s kind of unrealistic (and unsympathetic) to expect people to stop seeking answers to their problems just because you tell them that the seeking for answers is the problem. So how do you find your way out of the cycle of suffering without seeking solutions? It seemed like a cruel paradox.

Ironically, one day, out of the blue, something like an answer came to me. UG made all kinds of enigmatic statements that over the years have worked on me like how I imagine a Zen koan works. If I tried to actively sort it out, my mind would just get frustrated. But if I left them alone, ticking away like a timebomb at the back of my mind, occasionally some kind of understanding would eventually explode into my consciousness.

On this fateful day, one of these UG koans popped up in my mind again:

“The plain fact is that if you don’t have a problem, you create one. If you don't have a problem you don’t feel that you are living.”

I felt this to be a true (if harsh) assessment because I’d seen how myself and many of the people I worked with as a coach or yoga teacher experienced a lot of unnecessary suffering by creating problems where there really were none. Having problems to solve might give us a feeling of meaning and purpose, but if that’s what it takes for us to feel alive, we’re going to be stuck on a merry-go-round of suffering forever — what the Buddhists imagined as a wheel of samsara.

I’d wrestled with this problem in the past, but on this day, for whatever reason, a new idea burst forth:

What if I could simply help others feel more alive? Maybe then they wouldn’t need to create more problems in order to feel they’re actually living.

I felt renewed and invigorated by this revelation, and could glimpse an alternate path emerging that would lead me in a different direction than many of the experts and authorities I was encountering in the healing world. Suddenly, I could see that this path, based on this life-affirming insight I got from UG, would be a way I could finally integrate the three main paths of healing I’d been exploring: yoga, shamanism and depth psychology.

I’d found my unique medicine path and wanted to help others find theirs, by helping them discover and cherish the things that give them strength, inspiration and vitality.

The Yogic Approach

“The obstacles produce mental agitation, negative thinking, discomfort in the body, trembling and erratic breathing. With proper practice of steadying the mind, the obstacles cannot take root.”

— Patanjali Yoga Sutra 1.31-32

The yoga tradition I’ve been immersed in for over a decade comes from TKV Desikachar, who was a friend of UG Krishnamurti and personal yoga teacher to J Krishnamurti. His book The Heart of Yoga is an invaluable resource for Westerners looking for a better understanding of yoga principles and practice.

TKV Desikachar (1938-2016)

Yoga provides a multi-layered approach to reducing avoidable suffering and ultimately recovering more freedom, creativity and joy in our life. A brief summary cannot do justice to this rich and complex tradition, but I’ll touch on a few of the main ideas that relate to working with trauma in a general sense.

In the classical yoga tradition, it’s understood that all experiences, whether painful or not, create psychological impressions, called samskaras. These impressions can lead us to act and react in ways incongruent with present-moment reality and, in doing so, create more unnecessary suffering for ourselves and others. I sometimes imagine these impressions like the groove in a vinyl record. The deeper the impression (positive or negative), the more likely we are to get stuck in it, playing the same song over and over like the proverbial broken record.

One of the primary goals of yoga is to recognize when you’re stuck and get yourself out of the rut so you can act with freedom of choice.

The classical tradition associated with Patanjali and the Yoga Sutra emphasizes the mental sphere. Through radical self-inquiry we seek disidentification with the conditioned mind to reveal an inner observer or true self that is free of mental impressions. The process has many stages, but the Indian guru Ramana Maharishi sums it up pretty well with his famous self-inquiry question, “Who am I?” The idea is that we keep asking until we get down to a level of awareness that has no identification with anything less than the Self itself.

“The thought ‘who am I?’ will destroy all other thoughts, and like the stick used for stirring the burning pyre, it will itself in the end get destroyed. Then and there, Self-realization will arise.”

— Ramana Maharishi, Who Am I?

Other paths like Hatha and Kundalini yoga work primarily with the body and energy system through postures (asana), movement (vinyasa) and breathwork (pranayama). The basic idea is that through diligent and careful practice, we can gradually unravel and remove granthis, which are imagined as mental-emotional knots in the energetic body that block the flow of life energy and thus arrest our spiritual growth. When I learned about Carl Jung’s theory of the Complex — the complex bundle of thoughts, feelings, images and beliefs that forms around a formative experience — I was reminded of the granthis.

To me, the image of a complicated knot associated with a person or life experience that is blocking growth and creating unnecessary suffering offers a hopeful story and inspired pathway to healing for clients who feel trapped in the past and helpless to change what happened to them. In this case, trauma healing could be imagined as a process of slowly unravelling thoughts, feelings and beliefs that are wrapped up with a singular memory or experience.

I’ve found that for most of us, regardless of what story we choose to guide our healing journey, it’s good to start working with the body and breath because they are the most tangible, felt part of our experience and we can observe positive changes almost immediately. Over time, the practice of asana, vinyasa and pranayama helps to restore the body and nervous system to a more consistently balanced state. And while we wait for moksha, the tools we learn and the awareness we cultivate while practicing them help us recover more quickly from emotional triggers when they inevitably occur, thus reducing the potential to create yet more unnecessary suffering.

The Shamanic Approach

“Look at every path closely and deliberately, then ask ourselves this crucial question: Does this path have a heart? If it does, then the path is good. If it doesn’t, it is of no use.”

— Carlos Castaneda, The Teachings of Don Juan

As I wrote about in Yoga & Plant Medicine, and expanded upon in my Shamanic Yoga Breathwork videos, there are many parallels between hatha yoga and the shamanic traditions I’ve encountered.

In contrast to the typical Western therapeutic approach of going back into the story of your trauma, the indigenous Shipibo and Ashanikan healers I’ve worked with have no interest in your story. Their method of diagnosis is to read the energetic body of the patient while in ceremony with the help of their plant ally. Much like the hatha yoga tradition, they’re looking for energetic blocks or disturbances that are causing the physical or mental illness.

Juan Flores Salazar, Mayanuyacu Peru

When I asked Ashaninkan healer Juan Flores Salazar what he thought of trauma, he told me that it is when someone becomes obsessed with their personal story.

I’m reminded of James Hillman’s statement, “We are less damaged by the traumas of childhood than by the traumatic way we remember childhood as a time of unnecessary and externally caused calamities that wrongly shaped us.”

A Shipibo shaman, when I asked him what the main problem is with all the Westerners he works with, told me straight up: “It’s simple. You think too much, you read too much. You are too much in your head, not enough in your heart.”

According to many sources, the psychotropic plant medicines typically weren’t even given to the patient, it was only used by the doctor for diagnostic purposes. I visited a tobacco shaman in Iquitos once and we didn’t talk at all. He sat in front of me in a small dark closet and blew tobacco smoke over my body to see what was going on. He told me there was a small dark spot forming on my lung and prescribed blending a green banana with water and drinking it every morning for seven days. The shamans of the Shipibo tradition might spend hours singing to you to straighten out your energy lines or remove blockages. Other treatments I’ve seen include sweat baths, herbal remedies for topical application or ingestion, deep tissue massage, fasting and vomiting. No talk therapy.

It wasn’t until Westerners started descending upon the indigenous people of the Americas with their voracious appetites for novel experiences and exotic highs that the paradigm shifted to where it’s now taken for granted that you should be able to visit a shaman, pay them to give you ayahuasca, mushrooms or whatever, and force them to listen to your problems.

When I was teaching yoga at an ayahuasca center in Peru, I usually had to sit in on the individual consultations and group sharing circles even though I thought they weren’t helpful and were possibly even blocking the natural healing process. During the consultations with the new retreat guests, I saw the indigenous healers become visibly bored and exhausted by listening to the long-winded stories the “pasajeros” (passengers) told about their difficulties and traumas. I swear I’ve never seen people smoke and yawn so much. It’s interesting now to think about how they referred to guests as “passengers” rather than “patients.” Did they see them as nothing more than spiritual tourists on a trip carrying lots of baggage?

In many of these traditions, including the Santo Daime church where I started drinking ayahuasca, talking about your experience is discouraged. Yet, at the Western-run ayahuasca retreats, it’s not only expected that we all share our experience with the group but it’s seen as an integral part of the healing process. I disagree and think there’s some real wisdom in discouraging it.

If you were to ask an indigenous person why you shouldn’t tell your visions to just anyone, you might get a response about the sacredness of the vision or how it could make you vulnerable to a psychic attack by a sorcerer. But, outside of any superstitious or magical reasons, I think it also guards against heroic inflation or, on the other hand, reinforces the victim mentality that can occur when we identify too strongly with our story. Again, the Hero-Victim archetype plays a central role in the Western approach to healing trauma.

Another concept you find in many shamanic traditions is the idea of soul loss. The idea is that when someone experiences a shock of some kind, part of the soul can leave the body or, in other cases, it can be stolen by a malevolent spirit or black sorcerer. Symptoms of soul loss read like a running list of the most common mental health disorders among Westerners: depression, anxiety, addiction, sense of isolation, meaninglessness, lethargy, restlessness, obsessive thoughts… Surely a shaman would make the diagnosis that Western society is suffering from soul loss on a massive scale.

One of my concerns is that by going to other cultures in search of healing, we’re actually spreading the disease of modernity.

If we buy into the idea of soul loss as a source of so much of our suffering, then wouldn’t the prescription be to recover soul? Not so much in a literal shamanic sense, but by simply finding things that feed your soul — nature, friendship, music, dancing, good food, art, stories — and taking them like a medicine to restore and maintain the health of your soul.

A soul recovery approach would not only heal individuals, but could heal our culture, and prevent us from spreading the diseases of modernity to the rest of the world.

The Archetypal Psychology Approach

“I was driven to ask myself in all seriousness: “What is the myth you are living?” I did not know that I was living a myth, and even if I had known it, I would not have known what sort of myth was ordering my life without my knowledge. So, in the most natural way, I took it upon myself to get to know “my” myth, and I regarded this as the task of tasks…”

— C.G. Jung, CW5

When I was looking for a way to integrate and understand the experiences I’d had in my exploration of yoga and shamanism, I rediscovered the work of Carl Jung and some of the people who’d followed in his footsteps, most notably archetypal psychologist James Hillman and his student and friend Thomas Moore. Although I’d been introduced to their work many years before, I had to go through a lot of ups and downs on my own healing journey before I could fully appreciate their perspectives and ideas.

In their work, I found an orientation that aligned with my personal experience of moving beyond early childhood abuse and other traumas.

Even as a young boy, I had the intuition that my soul had chosen this life — this family, this place and time — for some reason.

James Hillman, 1926-2011

That there were certain things I had to experience so that my soul could learn and grow. I don’t know where I got that idea from — I certainly hadn’t encountered any Platonic thought in my working-class household or public school education. James Hillman might have suggested that perhaps it was my daemon who whispered it in my ear to encourage me to be strong and keep going along my life path.

When I re-read James Hillman’s book The Soul’s Code, I felt a strong resonance with the ideas he was proposing about the soul and its destiny. Following in the Platonic tradition, he expands on the old idea that our soul comes into this life with a destiny predetermined by the gods, and that our daemon or guiding spirit is there to help us find our true path.

If you’re interested in how archetypal psychology recontextualizes childhood trauma, I recommend at least reading the first chapter of The Soul’s Code and seeing how it resonates with you. Here’s a taste:

“We are, this book shall maintain, less damaged by the traumas of childhood than by the traumatic way we remember childhood as a time of unnecessary and externally caused calamities that wrongly shaped us.

So this book wants to repair some of that damage by showing what else was there, is there, in your nature. It wants to resurrect the unaccountable twists that turned your boat around in the eddies and shallows of meaninglessness, bringing you back to feelings of destiny. For that is what is lost in so many lives, and what must be recovered: a sense of personal calling, that there is a reason I am alive.

Not the reason to live; not the meaning of life in general or a philosophy of religious faith—this book does not pretend to provide such answers. But it does speak to the feelings that there is a reason my unique person is here and that there are things I must attend to beyond the daily round and that give the daily round its reason, feelings that the world somehow wants me to be here, that I am answerable to an innate image, which I am filling out in my biography.”

This approach to dealing with the inevitable “slings and arrows” of childhood isn’t about “healing” them or moving past them, at least not in the sense most people think. It’s about placing those painful and difficult experiences in the context of a much larger story than that of the wounded, abused and abandoned Inner Child.

James Hollis, another student of Jung wrote: “As Jung once put it humorously, we all walk in shoes too small for us. Living within a constricted view of our journey, and identifying with old defensive strategies, we unwittingly become the enemies of our own growth, our own largeness of soul, through our repetitive history-bound choices.”

When we imagine ourselves as part of a bigger story, the painful experiences of early life diminish in their power and ability to constrict us.

Jung himself put it this way:

“The greatest and most important problems of life are all in a certain sense insoluble. They can never be solved, but only outgrown. This ‘outgrowing’, as I formerly called it, on further experience was seen to consist in a new level of consciousness. Some higher or wider interest arose on the person’s horizon, and through this widening of view, the insoluble problem lost its urgency. It was not solved logically in its own terms, but faded out when confronted with a new and stronger life-tendency.”

This is really it in a nutshell. The way out of the limited (and limiting) narrative of the Traumadelic Culture is to discover, as Jung put it, the larger myth we are living, listen to the urgings of the soul as it tries to lead us toward our calling, and take up the task of caring for our soul and the soul of the world.

There is no formulaic prescription, no step-by-step method, so it isn’t something you can get from any expert. You gotta tune into your soul’s desires, listen to your daemon or guardian angel, follow your heart and take it one step at a time. Just the decision to listen to and trust your heart is the first step toward recovering your soul.

Western culture and the majority of people who make it up are suffering from a failure of imagination. Now, perhaps more than ever as we teeter on the brink of environmental collapse, nuclear war and a multitude of other threats, we need the ability, or willingness, to imagine radically different possibilities for how it all could be.

It will require imagining a better, brighter future that we probably won’t even be around to experience.

In order to bring ideas from the realm of imagination into material reality — without any expectation of reaping the rewards of the work — it will require a society of capable and courageous adults, not a society of self-obsessed wounded children.

Recommended Reading

We’ve Had 100 Years of Psychotherapy and The World’s Getting Worse, James Hillman & Michael Ventura

The Earth Has a Soul: C.G. Jung on Nature, Technology and Modern Life, edited by Meredith Sabini

Care of the Soul: A Guide for Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life, Thomas Moore

Soul Therapy: The Art and Craft of Caring Conversations, Thomas Moore